Examine the “hometown” you included in previous learning activities, considering whether or not it has been affected by loss of sustainability. Look back two hundred years and compare that “hometown” to what exists today.

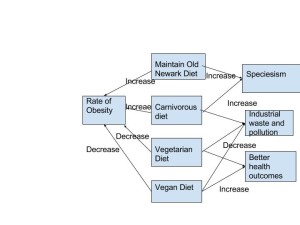

My birthplace of Newark, N.J. has the third-smallest land area of the major cities in the Unites States. The city is essentially a large basin which flows into the Passaic River. It is bounded on the east by large marsh areas. Two hundred years ago Newark had a number of small farms and undeveloped areas with a great deal of wildlife. Obviously, there were no automobiles, its population was measured in the tens of thousands and much of the “city” was unspoiled with little pollution

When I first considered this question I thought I would look back 100 years, but I found that even at that point Newark was starting to have difficulties. First, a few things that were done properly.

Newark hired Frederick Law Olmsted in 1867 to design and build Branch Brook Park, 360 acres of parkland, with now 4,000 cherry trees (largest collection in the US.) and a 24 acre lake. A very fortunate oasis. Newark also set aside land for several large parks in what is now the ‘downtown’ area. Though much of these parks are “lawn,” mown grass, a good portion is left ‘natural’ – with diverse habitats, and supports a good deal of wildlife.

How has it changed and what caused that change?

Beginning in the mid 1800’s unfettered industrial development created massive amounts of pollution – both of the ground and waterways. Over time Newark saw the following substances dumped: dioxin (which in many cases has not been removed, but ‘capped”) Agent Orange, oil (from the huge Exxon Bayway refinery) mercury, and other chemicals used in the factories which lined the Passaic, which was once thought of as the first ‘dead’ river in the country, having been thought to be past its point of resilience. Much of this pollution was, and still is, experienced in the poorer sections of Newark. Many people, even today, live literally on top of polluted sites. Certainly an example of environmental injustice. This situation, coupled which incredibly dense development (New Jersey is the most densely populated sate in the nation) results in a loss of non-human habitat, a loss of vegetation, poor air quality and enormous environmental health hazards.

Imagine what your “hometown” will look like, in terms of sustainability, and biodiversity, one hundred years from today. What actions, individual or community, would lead to this new reality?

We have a choice, don’t we? We can choose to be willfully ignorant of the effects of ‘our’ actions (the actions taken many years ago to cause this situation are an example of ignoring procedural justice and sustainability) and continue on this path, or we can take action to correct problem.

A multiple billion dollar cleanup project has just been announced for the Passaic River. A good start but certainly much more is needed. We can advocate for the recapture of “greenspace” through conversion of abandoned property.. Newark has lost population and there are a great many empty lots. These can be converted to urban farms or other types of greenspace, habitat for animals, birds, etc. “Green roofs” are a particularly interesting idea for this densely developed city. Also to be considered are infrastructure changes and a change from an automobile-centric lifestyle to mass transit. What is needed is intelligent development which balances human and non-human needs and long-term sustainability. Only if drastic action is taken will we have a ‘livable’ city in another one hundred years.

How will we get all of this to work? The primary ingredient is an educated, involved citizenry!

Mike Evangelista