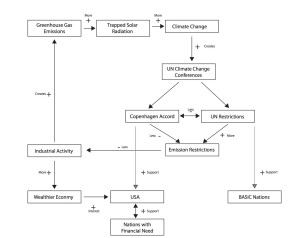

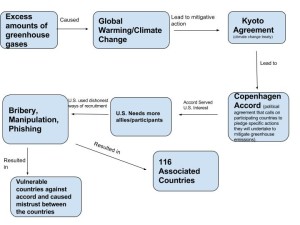

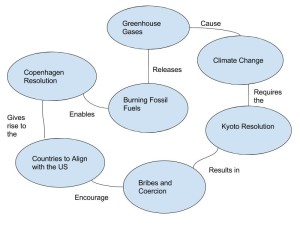

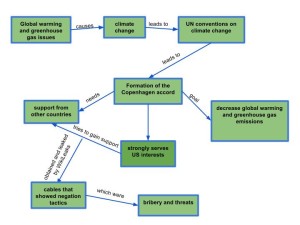

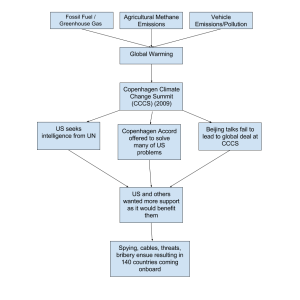

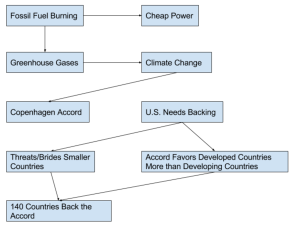

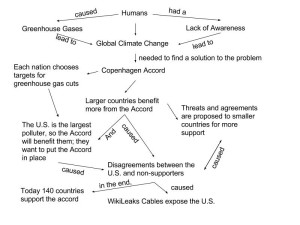

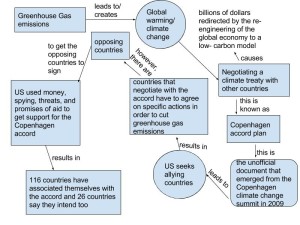

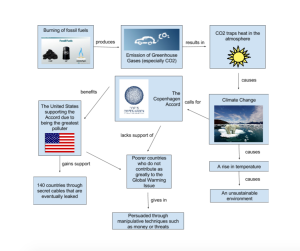

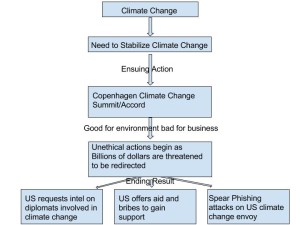

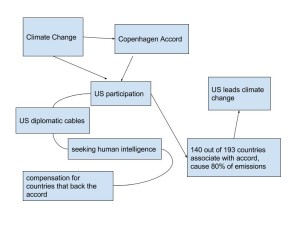

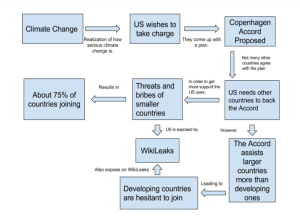

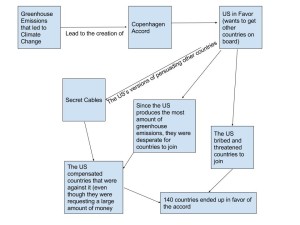

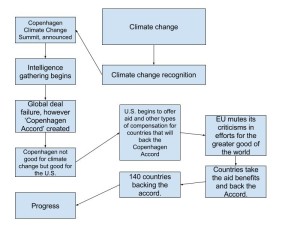

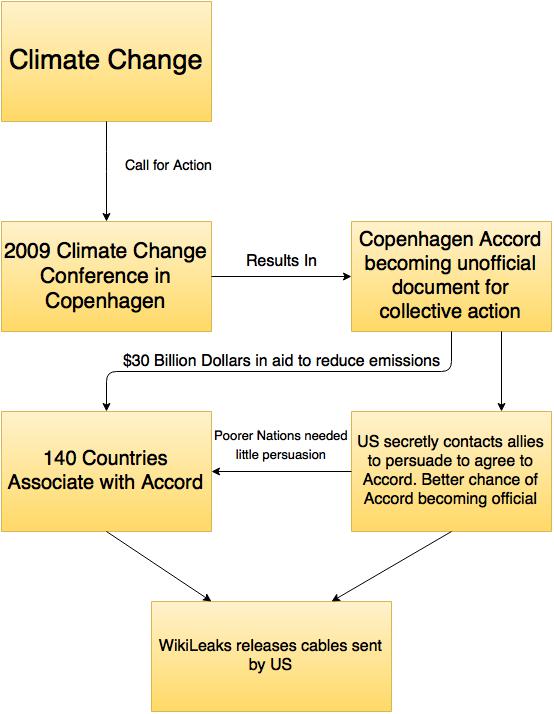

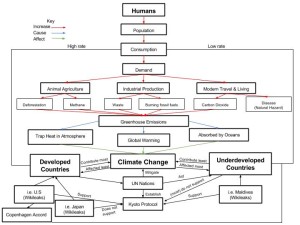

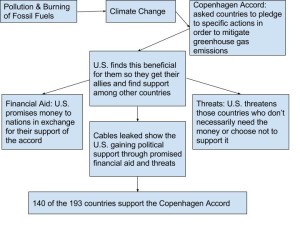

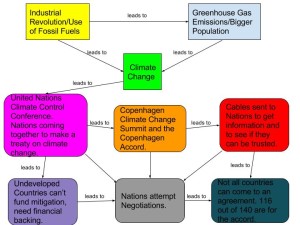

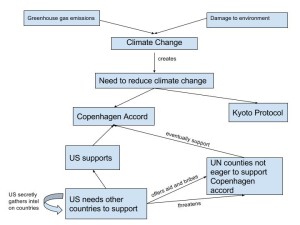

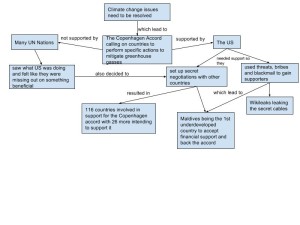

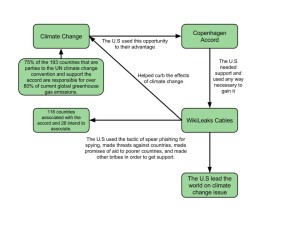

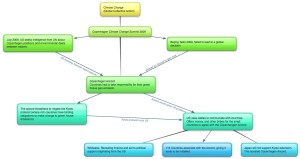

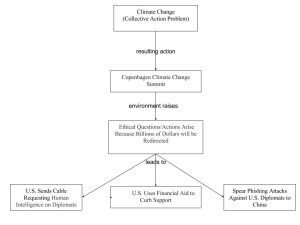

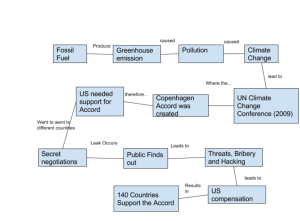

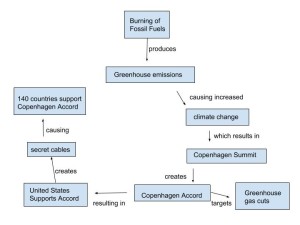

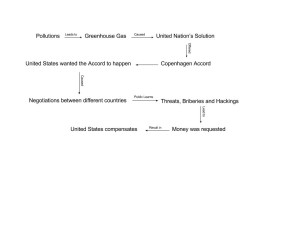

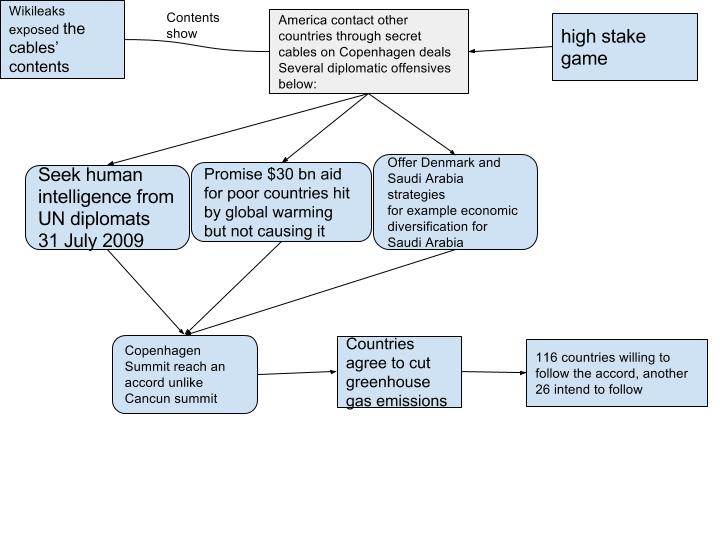

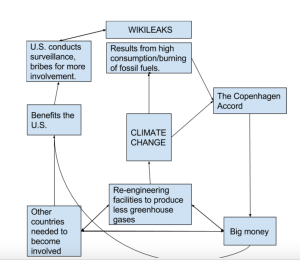

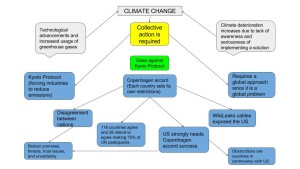

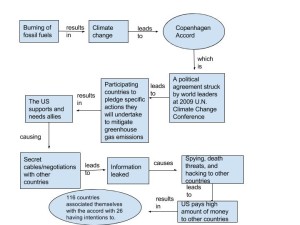

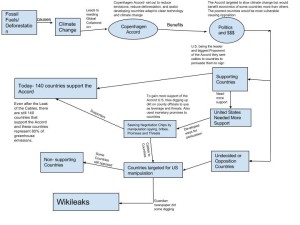

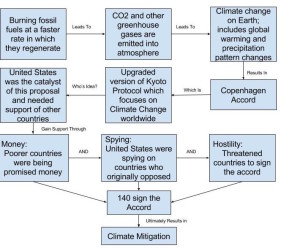

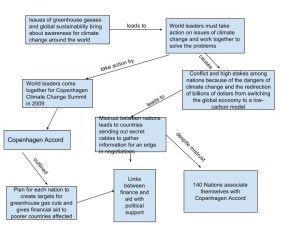

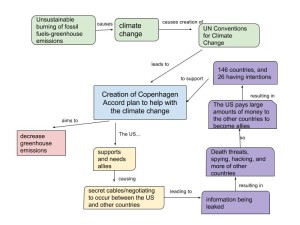

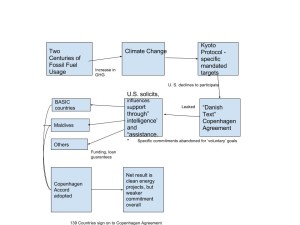

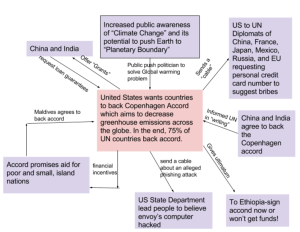

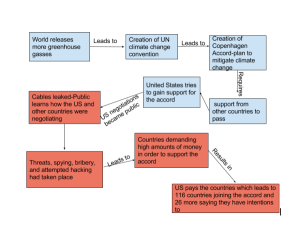

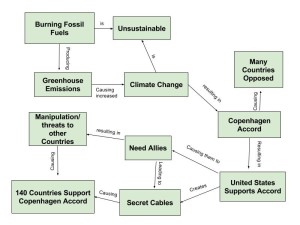

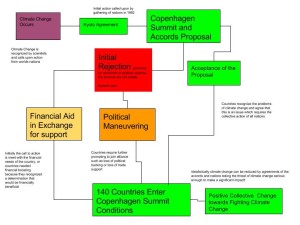

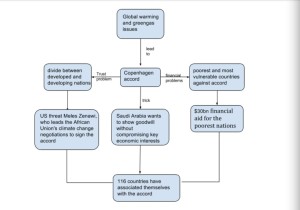

My systems diagram emphasizes the main components of the cable leaks revolving around the Copenhagen Accord. The accord is one of many proposals of the UN Climate Change Conferences to reduce green house gas emissions. The Copenhagen Accord is endorsed heavily by the United States as it reduces the binding obligations of large industrialized nations that the UN process has adapted. This would allow the United States to reduce its emissions in its preferred method, reducing the status of the economy. By reducing the emission restrictions, industrial practices can continue with limited obstacles. Industrial processes are some of the largest sources of green house gas emissions, considerably from fossil fuel excavation and use, which increase the amount of trapped solar radiation that raises the Earth’s surface temperature. Increased temperature is one of the many symptoms of climate change, to mitigate climate change global conferences (such as the UN Climate Change conferences). Industrial practices are also are a source of much economic wealth. Keeping industrial practices from restrictions that the UN process would otherwise induce is in the United State’s interest because of the large surge of wealth it provides for the country. To get other countries to support the Copenhagen Accord (that would allow this), the United States has allotted financial support to other countries in need to sway their position on the proposal. From the diagram, the opposing process listed in the article, the UN process, has support from the Basic Countries (Brazil, South Africa, India, and China) which would be less restricted from the process than the U.S..

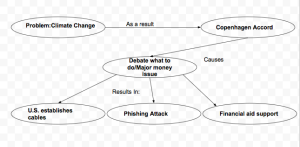

My strongest view on the cable leak is that the negotiations should not have been private. As representative members of the public, the State Department’s agendas should be that of the people they represent, and to know how the people would want to be represented the Department has to at least let the public know what is going on. This would slow down some negotiations, but the ends that are meaning to be achieved would be that of the nation and better represent “the people.” This is a community action problem, because individuals might want to continue with their gas emission activities instead of the intent of the UN conference to reduce emissions. However, considering the United States has taken a position already in interest more towards retaining industrial strength than emission reduction, involving the public wouldn’t lesson the nation’s intent of climate change mitigation.

To get supporters for the Copenhagen Accord, the United States has been negotiating aid for (participating) countries in need. Withdrawing aid for those who contend and increasing aid for those who concede influences these poorer nations to sway their votes in favor of the Accord. Although done underhanded, this is a common strategy in negotiations. For anyone to want to adhere to a decision, they must benefit in some way, and the United States has been giving these nations aid for their support on the decision.

This method for gaining support has allowed the consensus to swing largely in favor of the Copenhagen Accord. As for climate diplomacy, it is not being used properly as the Accord would not be able to restrict the overall emissions and just restrict particular practices the country itself allows. The U.S. is one of the largest emitters of greenhouse gases, so if every nation had to reduce their emissions by a certain percentage, the U.S. would be one of the largest affected. This method would be in the best interest of climate mitigation because those with smaller emission rates already do not need to reduce their footprint as much as those with larger ones. The U.S. is a nation that needs to greatly reduce its footprint so that reducing the impact of climate change is achieved. If the U.S. does not have greater restrictions for its large-scale emissions, the mitigation efforts wouldn’t be as productive.